Searching for the Mount Marshall Plane Crash

"Many factors contributed to this miracle, not the least of which was luck and timing. The date was August 9, 1969, a night of fair weather and moderate summer temperatures. These two factors eliminated a whole host of secondary problems that could have besieged the pilot, F. Peter Simmons, for weather and exposure often contribute to fatalities after one has survived the initial impact.

Simmons, a relatively inexperienced pilot, left the Islip airport in Long Island (New York) for a solo night flight up to the Adirondack Regional Airport in Lake Clear. He was flying home to the family camp on Big Tupper Lake, and family members were waiting to pick him up at the airport. He never arrived. His Cherokee 140 found a different runway to touch down on.

When Simmons' Cherokee 140 became ensnared in a downdraft as he flew over the High Peaks region, Simmons was forced to use every lesson he had learned in flight school and from his 350 hours of flight experience. He knew he was going down and could not stop his descent so he pulled the Cherokee's nose up and dropped his airspeed down to 65 m.p.h. Sensing impact, he switched the master and the mags off. The last thing he remembered was a slight thump from one of the wings, as if it clipped a branch. Then fate took over.

His plane had missed the rocky flanks of Iroquois by a scant few hundred yards on one side, and the slopes of Mount Marshall on the other. As if guided by pure luck, the plane came down in the flat of Iroquois Pass, just as the slope turns downward toward Lake Colden. To help matters more, the plane was less than a hundred feet off the only trail in that area of the forest.

The Cherokee was not equipped with a shoulder harness and Simmons paid a heavy price for it. The impact threw him forward into the instrument panel, shattering his cheekbone, fracturing his skull, crushing his left eye socket, and breaking his lower jaw. A leg, ankle, and wrist also broke in the crash. He was in rough shape and going nowhere. To compound matters and place him deeper in jeopardy, the Cherokee was not carrying a crash-locator beacon.

But not to worry, for campers down by the lakes below had heard the impact and told Forest Ranger Gary Hodgson about it. He called the State Police to offer his services and give the Civil Air Patrol a possible search parameter. The CAP sent 27 planes up over the area and at 4:45pm on August 10th, some fifteen hours after the crash, the fuselage of the Cherokee was spotted from the air. However the pilot incorrectly identified the crash site as being Mount Marcy and it wasn't until 6 p.m. that another pilot gave a well detailed description of the landing site.

Hodgson, Marcy Dam caretaker Al Jordan, and a dozen other rescuers, including five state troopers, assembled at Marcy Dam and set out for the crash at 6:45 p.m. Just as dusk was settling around them, at around 8:40 p.m., they found the Cherokee and Simmons inside. Incredibly, the Cherokee was fairly intact, resting at about 3,800 feet.

Jordan and Hodgson treated Simmons for shock, placing him inside a sleeping bag and lighting a lantern for heat. The next morning, and some thirty-two hours after the crash landing, Simmons was air lifted out by the Conservation Department's helicopter, stabilized inside by Dr. Herbert Bergamini and Dr. E. Addis Munyan, and safely on the terra firma outside of the Lake Placid Hospital by 9 am.

This was the first, and only, rescue in the Adirondacks by the Civil Air Patrol. Simmons recovery was slow and intensive, but there are few days that go by were he doesn't think of those all the people who helped save his life. From the campers who helped guide the initial search, to the CAP for pinpointing his location, to the rescuers for securing and stabilizing him, to the air lift and doctors who put him back together. Many people working together to save a life stranded on the MacIntyre Range. Simmons has repeatedly shown his appreciation by throwing summer parties in recognition of those who saved his life that fateful August night."

Source: https://www.vftt.org/forums/archive/index.php/t-21209.html

THROUGH AVALANCHE PASS

This was the 4th time in 7 months that I was heading up into the Adirondacks. With 46 ‘High Peaks’ to cross off, and being within driving distance, it is slowly becoming my wilderness home away from home.

The nervousness of novelty was being replaced with the comforting familiarity of these rolling hills and rounded peaks.

This time was different though. This time while also conquering another one of the 46ers, my goal was to find the crash site I had read so much about.

Starting once more at the Van Hoevenberg Trailhead, I signed the trail registry and took my first steps into this new adventure.

The two mile hike to Marcy Dam is nice and flat and served as a good warm up. I took a moment to stretch my calves as I took in one of the best views in the area.

It looked a bit different the last time I was here.

Continuing on, I turned South and followed Marcy Brook towards Avalanche Pass for a couple more miles.

The pass was flanked by two steep walls of rock between Mount Colden and the appropriately named Avalanche Mountain. As I climbed up into the pass, on my left was the debris field of avalanches past. Broken, decaying tree trunks among the boulders feeding life into new growth.

Not quite a canyon as much as two very close mountains, the air was noticeably different down here with humidity trapped between the steep walls. The micro climate felt like a hidden rainforest.

The view soon opened up onto the dominating landscape of Avalanche Lake. Here, the hike turned into a scramble over boulders placed here by glaciers thousands of years ago.

At one point with nothing but vertical rock walls, the pass becomes impassible if it weren’t for wooden catwalks bolted to the cliff face. This area is known as the “Hitch-Up-Matilda”s.

The local story behind the name comes from 1868 when a mountain guide waded through the water to carry one of his clients past this point. Her husband urged her to “hitch up” to sit higher on his shoulders. And so, oddly, the walkway was named.

The Mt. Colden Trap Dike from across Avalanche Lake

About a mile later, I passed the trail for the eastern approach of Algonquin Peak as I was visited with memories of my first trip out here a few years ago where I climbed the two highest peaks over three days (Algonquin and Marcy).

Finally I approached the southern shores of Lake Colden where I would be setting up camp for the night.

Not long ago, there used to be a lean-to shelter here overlooking the lake. It was recently moved in an effort to preserve the natural beauty of this area. Newer wetland regulations now require any campsite to be a minimum of 150 ft away from water sources.

Unfortunate, as this would make one hell of a campsite, but preservation takes priority in the wilderness.

So after gathering up some water I headed back into the woods and uphill to find a spot with almost as good of a view to wake up to.

To the Summit of Mount Marshall

Morning came as the light bathed the inside of my shelter with a blue glow. This was my first time out with the new floorless Black Diamond Beta Light shelter. I was testing it out for my upcoming Iceland trip as it is supposed to hold up well in high winds. There are a lot of pros and cons and trade-offs to this type of tent, so stand by on a possible full review later.

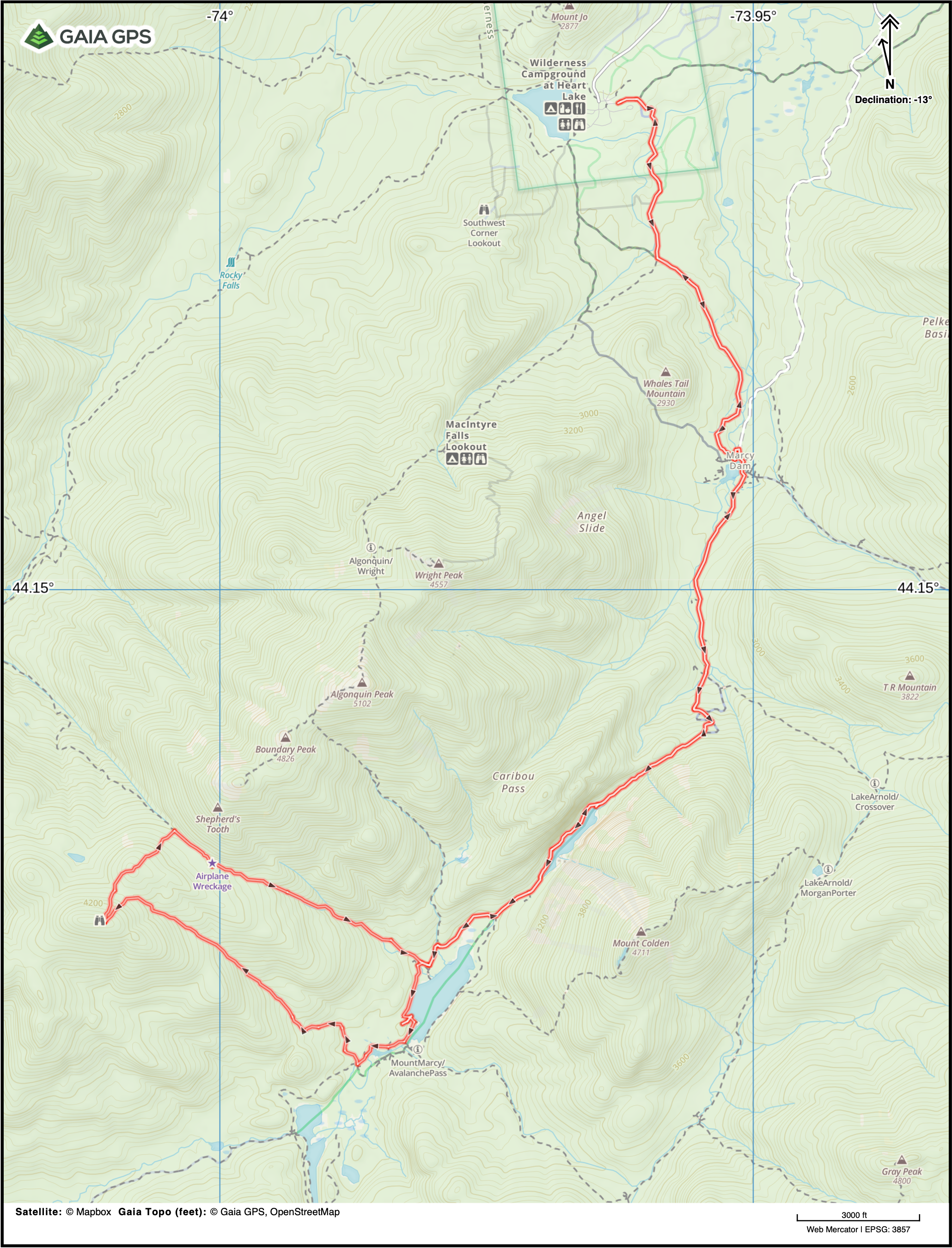

As I made my coffee, I looked over the maps for the coming hike. There were two ways up Mount Marshall from this direction. By either following the Herbert Brook Trail or Cold Brook Pass. Wanting to cross another High Peak off the list, I decided to head up to Marshall Summit first, and then over to the plane crash which can be found not far off of the Cold Brook.

The Herbert Brook Trail is not an officially maintained trail and is even missing from some maps. But it is travsered enough by hikers to have a somewhat established herd path. Without trail markers, it was at times difficult to stay on the path, but as long as I kept the brook by my side, I knew I was heading in the right direction.

Although slower and more difficult to traverse, part of me likes these herd paths. The lack of hard packed trail, overgrowth, and babbling brook pathways adds to the ‘wild’ nature of the wilderness.

Yep, this is the actual ‘trail’.

The Summit of Mt. Marshall is not the most popular of the 46 high peaks. With its three neighbors on the Macintyre Ridge (Wright, Algonquin and Iroquois) having bald peaks in the alpine arctic zone offering 360 degrees summit views, it's easy to see why the treed-in summit of Marshall might go overlooked by all but those looking to become an Adirondack 46er.

However that assessment is somewhat unfair, as the view from Marshall was still pretty amazing in its own right. So I chose to take some time up there to be present in the moment, and soak it all in.

Comparison is the death of happiness.

Finding the Crash Site

The path connecting the summit of Marshall to Cold Brook Pass was rough.

If I thought the way up was a seldom traversed herd path, I was truly in the wild now.

I have no photos or video from this section as I could barely stretch my shoulders apart as I passed through the trees. Although height is an advantage while rock scrambling, it served as quite a disadvantage here as I was continuously wacked in the face with branches and poked in the arm with broken tree limbs.

At times it felt more like a puzzle. There was a cliff face or two with no obvious way down and each move and foot placement had to be carefully plotted out.

Okay, there was one obvious and very quick way down.

After a very slow half-mile, I made it over to the Cold Brook Pass which treks over the mountain down both the western and eastern slopes. I turned east back towards Lake Colden and continued on.

The trail here opened up a bit as the path was the actual brook itself and I was rock hopping down the center of it.

Only a third of a mile down from the mini-peak of Cold Brook Pass, at roughly 3,840 ft there was a ten foot tall boulder sitting just off trail to the right of me.

From researching the trail, I knew this was the serendipitous marker for where to turn off for the plane crash.

Although only 100 feet from the trail, the plane was so obscured by the trees I was almost startled when I came upon it sitting just in front of me.

And so there it was. The small Cherokee 140 that crashed here a half century earlier. A fitting name for the aircraft as it came down just past Iroquois and Algonquin peaks.

I spent some time exploring the site. Imagining what it must have been like for the pilot and the search and rescue team all those years ago.

I enjoyed a victory cigar there sitting on the wing for a while, and then meandered my way back down to Lake Colden, returning to camp. I stayed one more peaceful night in the wilderness and set out back through Avalanche Pass in the morning.

If you enjoyed reading about this adventure and want to be the first to hear about the next one, make sure to subscribe to the YouTube channel to be notified when the next video and article are out!

Distance: 16.5 Miles

Elevation Gain: 3,881ft

Max Elevation: 4,364 ft